Javascript 101

1.4 Scoping

1.4 Scoping

Scoping

Unlike most programming languages (such as C/Java) which use Block Scoping, Javascript uses both Function Scoping and Block Scoping. Scoping is relevant when dealing with variable (or function) declarations.

Block Scoping

Depending on the language, blocks are defined using different syntax. For

example, in Java/C/Javascript, a block is created using { curly brackets }.

Python uses whitespaces for defining blocks.

//Java Example{ int x = 10; System.out.println(x); //10}

System.out.println(x); //x is not definedFunction Scoping

In JS, we have something called function scoping (i.e. a new scope is only created inside a function).

//Javascript Examplefunction foo() { var x = 10; { var y = 20; //does not make a difference if we were to enclose with { } } console.log(x); //10 console.log(y); //20}var keyword

As seen in previous examples, variables are defined using the var keyword and

it works on a function scoping manner. let and const were introduced later

on in ES6, which allows us to define variables with block scoping (to be

elaborated shortly).

//Javascript Examplevar x = 10;{ let y = 20;}console.log(x); //10console.log(y); //Error: y is not definedLexical Environment

To understand how the values in scopes are finally derived, it is important to introduce the concept of environment. This is not a concept specific to JS, but rather something common in programming languages. Simply speaking, it is a mapping of identifiers to values (variables and functions).

When we execute the following in the browser, 2 identifiers (x and foo) are

created in the global environment. In the case of the browser, this is

captured in the window object.

var x = 10;

function foo() { console.log("foo");}

console.log(x); //10foo(); //foo

console.log(window.x); //10window.foo(); //foo

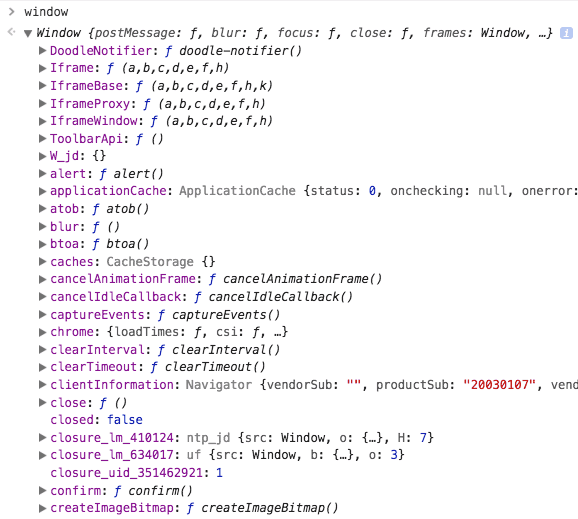

//global_env = [x: 10, foo: ƒ, ...] (window object)You can see the list of identifiers defined in the global environment by

executing window in the developer console and expanding the node.

Variables/functions can also be declared in functions. In which case, in addition to the global environment, there will be an environment created to capture the mapping of identifiers in the function. For example, consider the following code snippet:

//global_env = [x: 10, y: 'y', foo: ƒ, ...] (window object)var x = "10";var y = "y";function foo() { //env = [x: 'in foo'], global_env var x = "in foo"; console.log(x); console.log(y);}

console.log(x); //10console.log(y); //y

foo();//in foo//y

console.log(x); //10In the global environment (window object), we still have 3 identifiers (x,

y, and foo). In foo(), there is a local environment which contains an

identifier (x). In addition, there is also a reference to the parent's

environment, which in this case is the global environment.

When there is a need to determine the value of an identifier (e.g.

console.log(y)), JS will look up the value in its environment (global_env).

Likewise, when executing codes in a function, it will look up its own

environment to derive a value. If the identifier is found in its own

environment, it will use the value found in the mapping. However, if the

identifier is not found in its own environment (e.g. console.log(y)), it will

go to its parent's environment and repeat this lookup process. This illustrates

the concept of scope chaining.

So far, we have discussed the concept of environments but notice that the

heading for this section is Lexical Environment. Lexical comes from the

idea of lexical scoping/static scoping which means that the scope is

determined when the code is compiled (rather than at runtime or dynamic

scoping). Referring to the above codes, this means that the mapping of the

environment of foo() is predefined, which also meant that the values of the

identifiers in an environment can be determined beforehand.

Closure

So far, we have established that each function will have an environment (and its parent's environment). However, what happens when we have a nested function case which returns a function that is accessing a variable defined in the outer scope?

As an example, suppose we define a function foo which defines a variable x

and a nested function bar. foo returns bar as a function value which can

be called later.

var x = "global";function foo() { var x = "local"; function bar() { console.log(x); } return bar;}

var f = foo();f(); //localThe catch now is that since foo has been invoked (var f = foo();), it might

seem like we have lost access to the x defined in var x = 'local';. However,

running the above code snippets show that the local is correctly printed.

This is achieved through closures. A closure is the combination of a

function and its lexical environment. So in this case, when we define bar(), a

closure is created with its lexical environment (which can be used for looking

up identifiers).

//env1 = [x: 'global', foo: ƒ, f: ƒ, ...] (window object)var x = "global";function foo() { //env2 = [x: 'local', bar: ƒ], env1 var x = "local"; function bar() { //env3 = [], env2 console.log(x); } return bar;}

var f = foo();f(); //local//Another examplefunction foo() { var parent = "parent"; function bar() { var child = "child"; console.log(parent + " --- " + child); }

bar();}

foo(); //parent --- child//Yet another examplevar a = 1; //env1 = [a:1,...] (window object)function parent() { var b = 2; //env2 = [b:2], env1 function child() { //env3 = [c: 3], env2 var c = 3;

//when trying to access a: //can't find in local environment (env3) // try parent's environment (env2) //can't find in parent's environment (env2) // try parent's parent's environment (env1) //etc console.log(a); //1 } child();}parent(); //1Note that each function captures the reference to the parent's environment rather than keeping a copy of the parent's environment values. For example, consider a slight change in the above example, where the initial values of the parent's environment are changed.

var a = 1; //env1 = [a:1,...] (window object)function parent() { var b = 2; //env2 = [b:2], env1 function child() { //env3 = [c: 3], env2 var c = 3;

//when trying to access a: //can't find in local environment (env3) // try parent's environment (env2) //can't find in parent's environment (env2) // try parent's parent's environment (env1) //etc console.log(a); //resolve value of 'a' } child();}

//value in the parent's environment is changeda = 2; //env1 = [a:2,...]parent(); //2//Another examplevar a = 1; //env1 = [a:1,...] (window object)function parent() { var b = 2; //env2 = [b:2], env1 function child() { //env3 = [c: 3], env2 var c = 3;

//when trying to access a: //can't find in local environment (env3) // try parent's environment (env2) console.log(b); //resolve value of 'b' } b = 3; //env2 = [b:3,...] child();}

parent(); //3What the above examples show is that when the value of a variable is needed in the function, it will try to resolve the value of the variable with the name accordingly. The value of the variables in environments can change along the way during runtime. The values are resolved using the environments rather than resolved using a copy of the environment when it was declared.

One thing to be careful is that when declaring variables in functions, if you do

not use the var, const, or let keyword, the variable will be declared in

the global scope/namespace instead.

function foo() { //using var keyword var x = "def"; console.log(x);}

foo(); //defconsole.log(x); //x is not definedfunction foo() { //not using var keyword x = "def"; console.log(x);}

foo(); //defconsole.log(x); //defAs mentioned earlier, when defining variables or functions in the global scope,

the entries will be found in the global namespace (window object). However,

some of these variables or functions are only declared and used once. For

example:

//code snippet to put in the current date/time//to a divvar now = new Date();

var yesterday = new Date();yesterday.setDate(now.getDate() - 1);

function formatDate(date) { return date.getFullYear() + "-" + date.getMonth() + "-" + date.getDay();}

var element1 = document.getElementById("dateField1");element1.innerText = formatDate(now);

var element2 = document.getElementById("dateField2");element2.innerText = formatDate(yesterday);

console.log(window);//we will now have 5 additional properties://now, yesterday, formatDate, element1, element2The situation that we have above is also known as polluting the global namespace. While this often does not affect the behavior of our page/program, it has some negative implications:

- Variables/functions which will not be used later cannot be garbage collected, thus leads to wastage to browser memory

- Possibly slower performance (due to more memory consumption)

- Potential unexpected/unsafe behaviors (see below example)

Suppose we have a simple html file that includes 2 javascript files (Note that

when we include javascript files, it is as if we are copying and pasting the

codes from the included javascript files into the html document. This also mean

that the order by which the javascript files are included sometimes matter).

The expected behavior of loading this html file in the web browser is that 5

will be printed out after 5 secs (based on lib1.js).

<html> <script src="lib1.js"></script> <script src="lib2.js"></script></html>//lib1.jsvar a = 10;

//callback function that will print out value of//"a" after 5 secsfunction foo() { setTimeout(function () { console.log(a); }, 5000);}

//by right should print out 5 after 5 secsfoo();//lib2.jsvar a = 100;However, if we would open the html file in the web browser, we notice that 100

is printed out in the developer console instead. This is because lib2.js

declare variable a and initialize it to 100. This will not create another

property a in the window object since it already has the a property, but

this will modify the value of window.a to 100. So when the setTimeout

function is triggered 5 secs later, the value of window.a is no longer its

original intended value as written in lib1.js. This demonstrate a situation of

potential unsafe code execution.

Immediately Invoked Function Expression (IIFE)

A common way to address the above problems is to use an Immediately Invoked Function Expression (IIFE). The idea like the name suggests is to 1) define a function to wrap all these codes in a function and 2) invoke it immediately.

//define a function//notice that this function does not have a name so it is not added as a property//to the window object//we invoke it immediately by adding ()(function () { var now = new Date(); var yesterday = new Date(); yesterday.setDate(now.getDate() - 1);

function formatDate(date) { return date.getFullYear() + "-" + date.getMonth() + "-" + date.getDay(); }

var element1 = document.getElementById("dateField1"); element1.innerText = formatDate(now);

var element2 = document.getElementById("dateField2"); element2.innerText = formatDate(yesterday);})();

console.log(window);//we will not have the additional properties nowClassic Loop Pitfall

One of the classic pitfall/gotcha regarding function scoping is that it

might behave differently from what we think it should (especially if you have

prior programming knowledge). Consider the following HTML code example with 5

buttons. In each HTML button, we can assign an onclick handler, which we hope

to show the button index. It turns on that when you click on any of the buttons,

it always show 5 (instead of the respective index) :angry:.

<button>Button 0</button><button>Button 1</button><button>Button 2</button><button>Button 3</button><button>Button 4</button>Why does this happen?

Recall the concept of function scoping. A closure is created when a function

is declared. On the global scope, the variables are defined in the web browser's

window object. When we declare the variable i (var i), i is declared and

assigned the value of 0 (var i = 0) at the start. For each iteration, we

declare a new function and assign to the onclick handler of each button. When

we click on the button, the respective onclick handler will be triggered. In

which case, it will try to evaluate the value of i. Since i is not defined

in this function, it will look up the value of i in the parent's

environment.

//global scopevar buttons = document.getElementsByTagName("button");for (var i = 0; i < buttons.length; i++) { //global scope buttons[i].onclick = function (e) { //local scope alert(i); };}The reason why the value 5 is shown for all the button is because during

runtime, the final value of i will be 5 (in which case it will break out of

the for loop).

| Iteration | window's env | description |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | [...., i: 0] | i is declared and assigned the value of 0 |

| 1 ... 4 | [...., i: 1] | value of i in the window's environment changes from 0 to 4 |

| 5 | [...., i: 5] | value of i changes to 5 and i < buttons.length evaluates to false and break out of loop |

How can we resolve this?

One way to resolve this is to create the variable i in the closure for each of

the onclick handler. Unlike the previous example where i is not defined in

the function (and not defined as a function parameter), we now define it as a

function parameter so that i will be a variable in the local environment. i

in this local environment is mapped to the value of the first function parameter

(pass by value). This is to ensure that when we are assigning a function to

each of the button onclick handler during runtime, there will be a different

copy of i created for each iteration - that is the purpose of

function(i){ ... }(i);. This is similar to IIFE except that we supply a value.

Since each button onclick handler requires a function declaration, we then need

to return a function(e){ ... } like before.

If you find the above codes confusing, try renaming i to i2.

var buttons = document.getElementsByTagName("button");for (var i = 0; i < buttons.length; i++) { //define a function that takes in a parameter buttons[i].onclick = (function (i2) { //we name this parameter as i2 //we could just name the parameter as i like the example above //if we name it as i, it will overshadow the i variable in the for loop

//there is a mapping of i2 to a value in this local scope return function (e) { alert(i2); }; })(i); //keypoint is that we need to supply current value of i in tho this function}After executing the codes:

| Button Index | window's env | Button onclick's env |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | [...., i: 5] | [i2: 0] |

| 1 | [...., i: 5] | [i2: 1] |

| 2..3 | [...., i: 5] | ... |

| 4 | [...., i: 5] | [i2: 4] |

let/const keyword

The solution above takes some getting used to. Thanks to ES6, there is an easier

solution for this by using the block-scoping variable declaration syntax: let

and const.

var buttons = document.getElementsByTagName("button");for (let i = 0; i < buttons.length; i++) { //i is only available within this block buttons[i].onclick = function (e) { alert(i); };}

console.log(i); //Error: i is not definedlet allow copies of the variables to be created within a block { } and makes

it only accessible within the scope. Note that we can declare a variable that

has already been declared in the parent's scope.

let x = "global";{ let x = "parent"; { let x = "inner"; console.log(x); //inner } console.log(x); //parent}console.log(x); //globalconst like the name suggests allows you to declare constant variables.

const a = 10;a = 100; //Not allowed => Error: Assignment to constant variableconst a = 10;const a = 20; //Not allowed=> SyntaxError : Identifier 'a' has already been declaredHowever, you can create const with the same name as its parent.

const x = "global";{ const x = "parent"; { const x = "inner"; console.log(x); //inner } console.log(x); //parent}console.log(x); //globalWhat exactly is a const?

After seeing the effect of const above, it is important to examine what

exactly is a const. Which of the following option(s) do you think is/are

possible way(s) to describe it?

- It is a variable where its values are immutable (i.e. its value cannot be changed)

- It is a variable where the reference cannot be reassigned

- It is like the

finalkeyword in Java

Let's look at each case :

1. It is a variable where its values are immutable (i.e. its value cannot be changed)

We will be covering objects and arrays next but

you will realize that const does not prevent us from modifying the values

unless it is a primitive type (e.g. number, string, boolean, etc).

//define an arrayconst array = [1, 2, 3];

//append a new elementarray.push(4);

console.log(array); //[1, 2, 3, 4]//define an objectconst person = { firstName: "John", lastName: "Doe" };

//change name of personperson.firstName = "Jane";

console.log(person.firstName, person.lastName); //Jane Doe2. It is a variable where the reference cannot be reassigned

The examples we see on top is exactly the property of const. It does not allow

us to reassign a new variable/value to it.

3. It is like the final keyword in Java

It seems like const acts like the final keyword in Java. We are not allowed

to reassign another value to it.

final int a = 10;System.out.println(a); //10

a = 20; //Not allowed => SyntaxError : cannot assign a value to final variable aSomething to take note of the final keyword in Java is that we do not need to

initialize its value when you declare the final variable. Java does ensure

that you can only initialize its value once, but you can always initialize its

value later.

final int a;a = 10;System.out.println(a); //10const on the other hand, works slightly different from the final keyword in

Java. You have to declare and initialize its value in the same statement.

const a; //Not allowed => SyntaxError : Missing initializer in const declarationa = 100;So, we conclude the following:

- It is a variable where its values are immutable (i.e. its value cannot be changed) :x:

- It is a variable where the reference cannot be reassigned :white_check_mark:

- It is like the

finalkeyword in Java :x:

No hoisting for let/const

//var case//var a declaration is hoisted//a is assigned value of 10var a = 10;console.log(a); //10//var case//var a declaration is hoistedconsole.log(a); //undefinedvar a = 10;//let caselet a = 10;console.log(a); //10//let caseconsole.log(a); //Error: a is not definedlet a = 10;//let caseconsole.log(a); //Error: a is not definedconst a = 10;